Radical women have long been seen as troublemakers. Men who support them were not considered to be any better. Over 100 years before the modern #MeToo movement, there were hundreds of highly-educated people that demanded reforms. A government by the people had to protect all people not just the wealthy. Instead of just demanding that local governments provide decent housing and livable wages, they professionalize the fields of social work and sociology. These men and women started settlement houses, ran for municipal office, and tirelessly fought for the rights of working women, children, and immigrants. Below are 18 famous radicals that fought for birth control, workers rights, juvenile court and so much more.

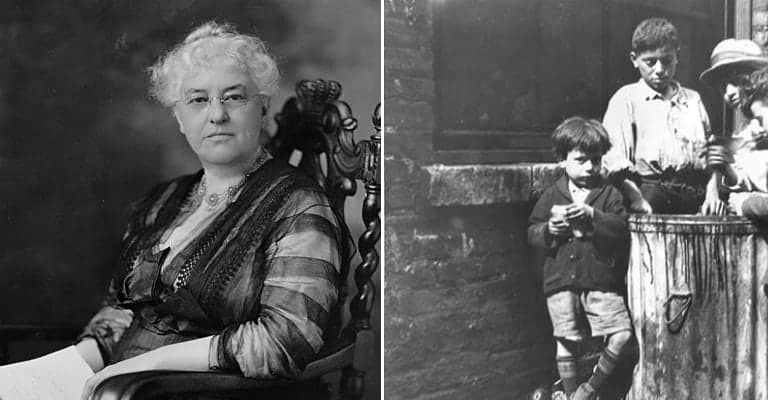

18. For the Love of Jane and Workers’ Rights: Ellen Gates Starr

Ellen Gates Starr was intellectual and passionate. Born in 1858 in New England, her family migrated to northern Illinois when she was young. Not wealthy but not poor, Ellen attended the Rockford Female Seminar where she expanded upon her passion for the arts, literature, and idealism. Ellen was vivacious and loved headed debates about politics and social issues. Topics that respectable women were to stay away from. Throughout her life she attempted to control her temper, but it was this very temper that led her Chicago’s near west side to become one of the founders of the field of social work.

Ms. Starr had to quit school for financial reasons. She moved to Chicago and became a school teacher. During the summer of 1888, Ellen toured Europe with her dear friend from college, Jane Addams. While in London the women visited Toynbee Hall, a new place devoted to helping the working poor. The women were gobsmacked and returned to American with vigor. They created a plan, found property, and opened their own settlement house in Chicago’s near west side neighborhood in September 1889. The women called their “social experiment” Hull-House.

Workers’ rights, eliminating child labor, and promoting the importance of education had long been passions of Ellen Gates Starr. She became a member of the Women’s Trade Union League and helped organize strikes f in 1896, 1910, and 1915. While walking a picket line during a 1914 restaurant workers’ strike, her impassioned behavior got her arrested. Her arrest made her more committed to the labor rights movement. In 1916, she joined the Socialist Party and ran for 19th Ward Alderman. She lost the election but had made headway in exposing the detrimental impacts of ward politics in Chicago’s immigrant and poor neighborhoods.

Ellen Gates Starr loved Jane Addams and for a time the women lived in what has been described as a “Boston Marriage.” No records exist of this relationship, it can only be gleaned from observers’ accounts. Sometime before 1920, Jane Addams ended her intimate relationship with Starr and she was devastated. She became a Roman Catholic and distanced herself from the settlement house that she co-founded. After spinal surgery in 1929 left her paralyzed from the waist down, Starr removed herself to a convent in New York where she died in 1940.