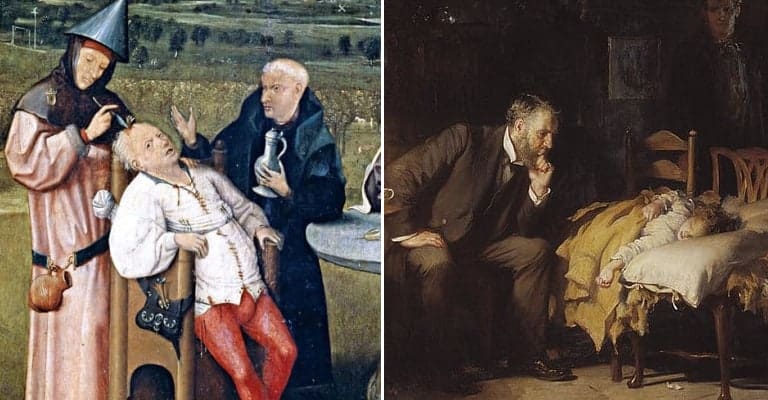

The practice of medicine is among the oldest professions in the world, responsible for the preservation and prolongation of countless human lives. Today, prospective medical treatments and procedures undergo rigorous testing, studies, and replications to ensure that they are both safe and effective. Unfortunately, these standards were rarely, if ever, adhered to by our ancestors, who instead subjected one another to unscientific and dangerous medical techniques. Whilst some merely proved ineffective, founded upon benign superstitions, others were immensely harmful and contributed to a lasting fear of doctors within certain cultures due to the increased likelihood of death from receiving medical attention than no treatment at all.

Here are 18 historical health practices that were just as, if not more likely to kill people than simply doing nothing: