Freedom of the press and speech are guaranteed to the American people by the First Amendment to the Constitution which was written, not because the American government thought it needed to create freedom of expression, but because in our early history there had been so many attempts by government to suppress it. Even with the protections of the First Amendment, the United States ranks 41 out of 180 countries in terms of press freedom. Freedom of speech is regarded by Americans as one of the most fundamental of all freedoms, yet it has always been one of the most controversial and has been challenged by the government, businesses, and individuals throughout history.

Communities reserve the right to restrict speech and art based on morality and what is considered by some, though not all, to be obscene. In 1973, the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment does not protect obscenity, though what is or is not obscene is a subjective judgment in many cases. Nor does the First Amendment fully protect citizens from corporate censorship as a protection for employees. It does protect the citizen from government censorship, but American history includes many instances where the government tried to circumvent or evade the First Amendment to suppress information or silence its citizens.

Here are ten examples of the government attempting to censor or silence the American citizen or the press and its reasons for doing so.

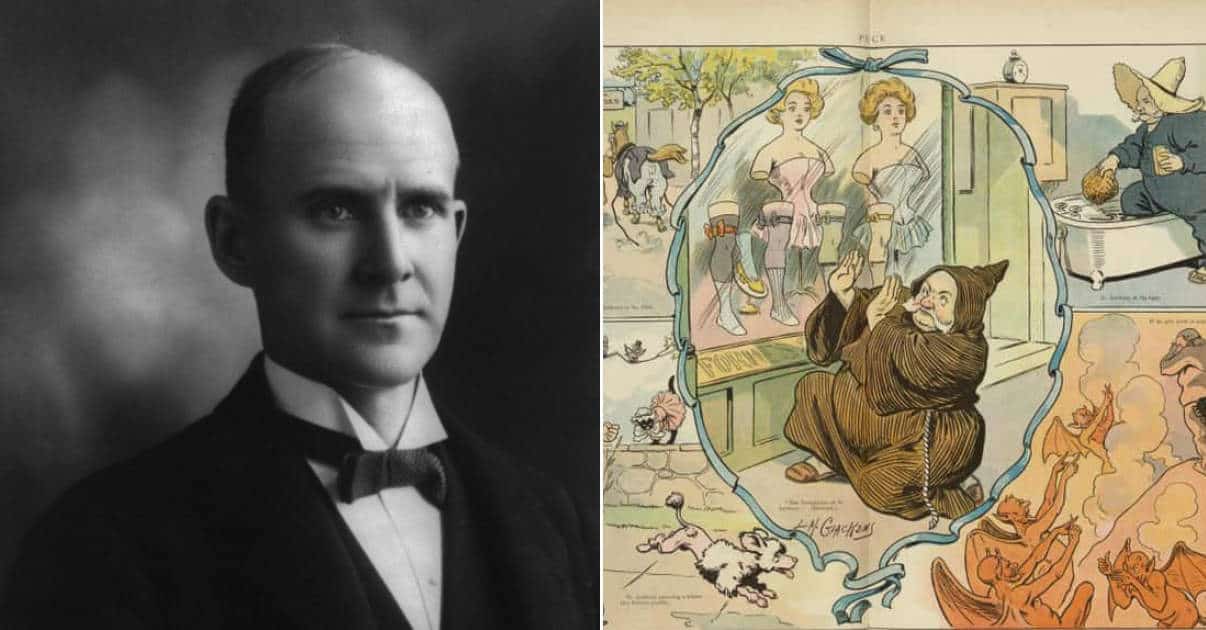

The Comstock Law and the use of the Post Office

The suppression of what certain individuals consider amoral behavior and attitudes has long been a target of government suppression through censorship. During the days of Plymouth Colony, the militia was used when it was learned that an enclave of settlers was enjoying the writing and singing of bawdy songs and verse, not in keeping with the prim image of the Separatists, for example. The First Amendment prevented the use of the military to suppress speech deemed unsuitable, but the federal government had other means at its disposal to suppress what it felt should not be before the eyes of the citizens.

In 1873, the Post Office was a Department of the Executive Branch, and the Postmaster General was a Cabinet level position. During the Civil War pornography among the troops of the contending armies of North and South became widespread. After the war many groups, among them the YMCA, found the pornography intolerable, believing it led to immorality and unwanted pregnancy. One of these moral guardians was Anthony Comstock, who also argued against the use of any form of birth control as immoral and destructive to the public character.

Comstock managed to get himself appointed as special agent to the YMCA’s Committee for the Suppression of Vice. There he drafted a law which made it illegal to send obscene or immoral literature through the United States Post Office. A similar law was already on the books, but it did not include newspapers, because of that pesky annoyance, the First Amendment. Comstock worded his new law so that newspapers could be included if they violated his and other’s version of what is or is not obscene.

This new bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Grant in 1873, called the Comstock Law in tribute to its author. Soon many states passed even more restrictive morality laws, collectively called Comstock laws. The Comstock Laws restricted the distribution of pornography through the mail, making it a federal offense to do so. It also restricted the distribution of information regarding abortions and the use of contraceptives, contraceptive devices, or information where such devices could be obtained.

At the time many newspapers carried advertisements for such devices and patent medicines which claimed contraceptive properties, under the law they could no longer be sent through the mail. What was considered obscene by Comstock covered a broad range of topics. Textbooks which discussed the anatomy of the reproductive system, and the reproductive cycle in women, were obscene by his standards.

Many of the governing bodies of the states and local communities used the umbrella provided by the Comstock Law to enforce yet more rigid standards for obscenity and immoral behavior. These were often called Comstock Laws as they were inspired by the federal standard, and many have been overturned by the courts or repealed by the state legislatures. The federal Comstock Law was repealed in 1957 but its definition of obscenity, including anything which “…appealed to the prurient interest of the consumer”, is still cited in obscenity cases today.