These days, queens and princesses have their babies in the safest and most comfortable environments possible. They are also offered privacy for the occasion, even if there is huge public interest in the event. However, this was not always the case. Far from it, in fact. Indeed, for centuries, in royal circles as in society in general, a woman’s body was not really her own. Rather, it was owned by men, by the church or by the public.

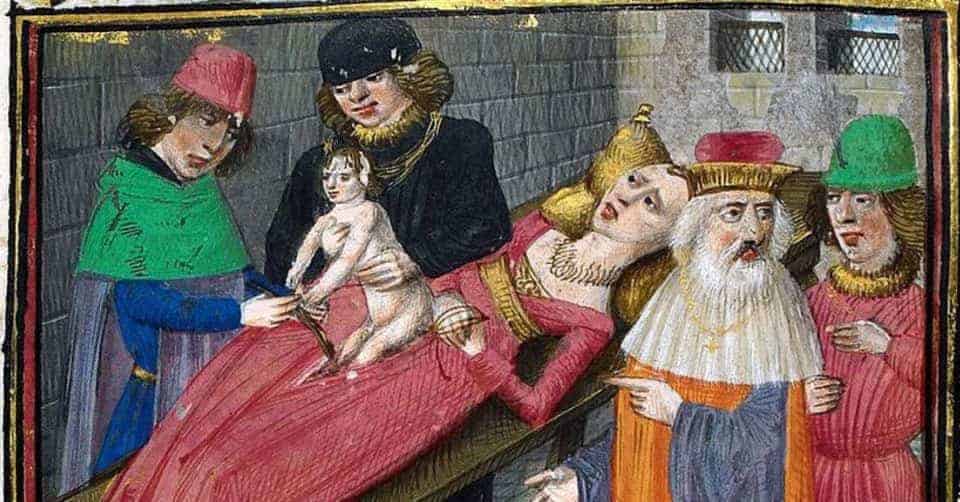

This meant that, from the Middle Ages, through Tudor times and even past the Regency era in England, royal births were public spectacles. They would attract huge crowds, with many even witnessing the birth itself. What’s more, a royal birth was expected to follow strict traditions and protocols, not all of which had the mother and baby’s best interests at heart. As the years progressed, the stifling traditions gradually gave way to modernity. But still, progress was largely slow in coming. After all, Prince Charles, first in line to the British throne, was born in Buckingham Palace, as was the custom. It’s only very recently that royals have been having their babies in hospitals.

So, here we have ten of the strangest customs and traditions attached to royal births in centuries past:

When it was time, there would be a royal procession to the birthing chamber

In centuries past, women – even queens and princesses with access to the finest medical minds of the time – could often be four, or even five or six, months’ pregnant before they knew they were expecting. After all, there were no home pregnancy tests in the Middle Ages, plus many of the symptoms normally associated with pregnancy might be dismissed as any number of common diseases or ailments. However, once it was known that a royal lady was with child, plans were put in motion for the birth – including all the pomp and ceremony that was to come even before she went into labor.

In 1500s England, for example, there was a Royal Book dictating what should be done in the build-up to a birth within the inner court. Even if the expectant lady herself was in pain or discomfort, procedures still had to be followed. So, Greenwich Palace was abuzz in 1533 as the queen got ready to give birth to the future Elizabeth I. As was the custom, around a month before she was due, the mother-to-be would attend a special mass in which the priest would ask for the birth to be blessed. After this, she would hide herself away from the public eye and even from the rest of the royal court in a process known as ‘lying in’.

The amount of interest in a royal birth is hardly surprising. After all, there could be a lot at stake: wars were fought when a queen gave birth to a girl rather than a boy, and any problems could also result in bloody dynastic struggles, with nobles and even commoners called up to fight. This idea of a royal birth being a public spectacle continued into the Regency period in England. Then, there was an expression for heading off to see the queen set off for her church blessing and begin her ‘lying in’ – people would “go to town” to try and catch a glimpse of the royal mother-to-be. Even today, royal births are announced to the public right away – in England, for example, courtiers still post hand-written notes in front of the gates of Buckingham Palace to announce a new addition to the Royal Family.