The history of the American Labor Movement has run concurrently with the development of the nation, affecting political development, social reforms, industry, the economy, healthcare, recreation, agriculture, immigration laws, and virtually all aspects of aspects of American history. Beginning as a primarily agricultural nation with a small collection of artisans and mechanics, the United States emerged as an industrial colossus by the twentieth century, leading the world in the production of consumer products and standard of living. The United States has since slipped from the pinnacle in both of those categories, but its labor force remains one of the most diverse on earth in terms of skills.

It was a long and difficult road accepting the movements which protected – and still protect – the rights of workers in the United States, as well as ensuring a safe working environment, fair compensation, and relative job security. Labor unions remain controversial in America, with some blaming them for the decline of American heavy manufacturing, having created labor costs too high for producers to absorb. Right to work states are regarded as essential by those determined to keep manufacturing in America, others view them as an un-American assault on the union workers. The controversies over labor began at the dawn of the nation, and will continue to be part of the American landscape for the foreseeable future.

Here are ten highlights of the American labor movement which developed over the course of the nation’s history.

Early instances of collective bargaining in America

Long before the series of squabbles with Great Britain which led to the American Revolution, American workers joined together to improve their lot regarding their employment and income. As early as 1636, Maine fishermen joined together in a strike, demanding a higher price for the cod they delivered for salting. The strike was a successful one. In the larger colonial towns, artisans joined together, not to control prices for their services but to establish markets and regulate their apprentices. Manufacturing was done by small firms, usually a master, one or two journeymen workers, and apprentices who were learning the trade, often as indentured servants.

Following the American Revolution manufacturing grew rapidly in the Northern American towns throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. By the end of the War of 1812 journeymen workers outnumbered master craftsmen in the cities, and in several they joined together to obtain improvements in their compensation through either increased pay or decreased working hours for the same pay as previously. These cases were frequently referred by craftsmen to the magistrates, and the courts nearly always found the collusion to be illegal criminal activities, fining the workers, and in cases where they were unable to pay, jailing them for a time.

The developing case law led to the consideration that laborers had the right to gather in guilds or unions, but not to use gathering as a means of applying collective bargaining regarding wages or work conditions. Such activity was held to be illegal in emerging American common law. In 1842 a Massachusetts Supreme Court decision softened the conspiracy doctrine, finding unions to be legal if they were formed for a legal purpose and used legal means. The decision, Commonwealth v. Hunt is sometimes cited as a landmark of the labor movement, but it affected only Massachusetts. Conspiracy convictions of labor organizers continued in other states.

Through the first half of the nineteenth century labor organizations were local affairs, and covered workers in a single profession, such as the Journeymen Bootmakers Society in Boston, the organization found to be legal in Commonwealth v. Hunt. During the American Civil War Northern manufacturing grew exponentially, and following its end the National Labor Union (NLU) was formed by William H. Sylvis, a member of a local ironmolders union in Philadelphia. Sylvis planned to create an organization of the different unions and labor societies for various trades into a single entity which covered workers in all trades.

The NLU was moderately successful for a time, but the union experienced recruiting difficulties, competition from local unions for membership, and poor leadership and communication. It reached a peak of around 600,000 members in 1869 but declined rapidly in 1870. A similar organization for workers in the shoe industry formed in Wisconsin in 1867, grew rapidly in the state, declined even more rapidly, and collapsed during the Panic of 1873, as did the NLU. The goal of national labor organization remained elusive.

In 1869 the Knights of Labor were formed, grew slowly for a decade, and then experienced a burst of growth in the 1880s. In the railroad industry which boomed in the decade following the Civil War, numerous unions developed based on the different trades demanded by the railroads. These included the Brotherhood of Railroad Engineers; the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen; and the Order of Railroad Conductors, among others. The railroad unions considered the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to be too radical and avoided affiliation with them, consolidating power among themselves.

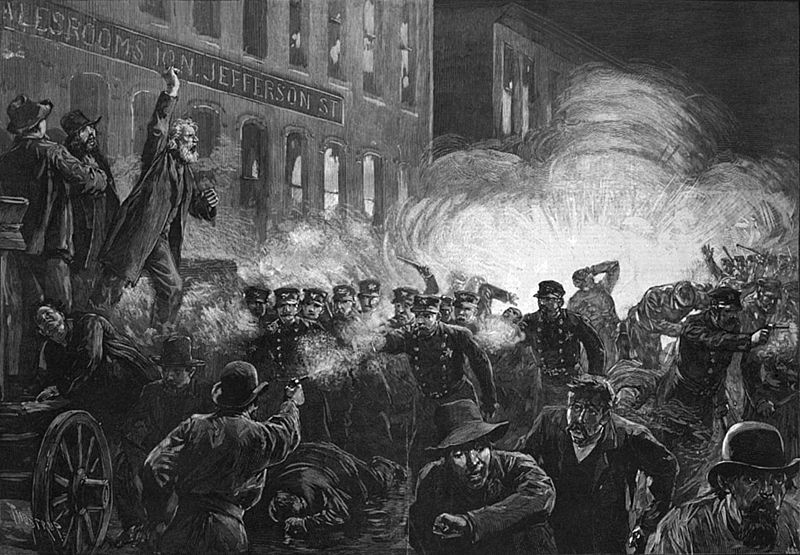

Some railroad workers individually joined the Knights of Labor, especially during its period of explosive growth which started in 1880. The Knights of labor stressed programs for workers and their families, including the development of recreation facilities and educational programs. The Knights also used tactics which included them being associated with the anarchist movement which began in the United States. The association was an inaccurate perception which was fed by the anti-labor movement, but after the Haymarket Riot in 1886, in which seven policemen were killed, the Knights could not shake the reputation, and most of its members defected to the less radical AFL and the railroad brotherhoods.