Americans take them for granted today, as symbols of the United States and of the community in which they are located, but the construction of man-made national landmarks was in each case a struggle. Chief among the many obstacles they all faced were the twin challenges to American progress – money and politics. Engineering challenges were daunting in many cases, but they were dwarfed by the opposition voiced to the projects based on political motivations, now largely forgotten. The evidence of the opposition can be seen in some of the monuments and landmarks today by those aware of them, for example in the Washington Monument on the National Mall.

About one third of the way up the Monument the color of the exterior stone changes. This change occurs because the stone for the upper two thirds came from a different quarry than that below. Construction of the monument was stopped for more than two decades, as the lack of funds, a struggle for control of the project, and the American Civil War intervened. When construction resumed the original source of the stone was no longer available, hence the change in color. The monument was completed during the latter years of the nineteenth century, giving the lie to the assertion that it was built by slave labor, since slavery in the United States was abolished by that time.

Here are some facts about some of the National Landmarks which are a part of life in the United States.

The Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty is often referred to as a gift from France, which is a somewhat simplistic way of describing the icon. The copper statue was provided by France, but from its inception the project was seen as a joint venture between the French and the United States, with France providing the statue itself, and the Americans providing its pedestal and paying the costs of its construction on the site. Conceived by Edouard Rene de Laboulaye in the 1860s, designed by Frederic Bartholdi, and built by Gustave Eiffel, the statue was completed in phases, with both the head and the torch displayed publicly to enhance fundraising for its completion, before it was installed on Bedloe Island in New York Harbor.

For his inspiration Bartholdi selected the Roman goddess Libertas, to whom temples were erected on the fabled Seven Hills of Rome. Libertas appears on the Great Seal of France (1848), to which Bartholdi referred in his design. In her Roman appearance Libertas frequently held a rod, symbolic of manumission by the rod, an act in which freedom was attained through the actions of a magistrate, who would dub a slave with a rod rendering them free. Bartholdi substituted a torch, symbolic of light and freedom through knowledge. As he worked on his varying designs Laboulaye created a consortium through which the statue would be funded.

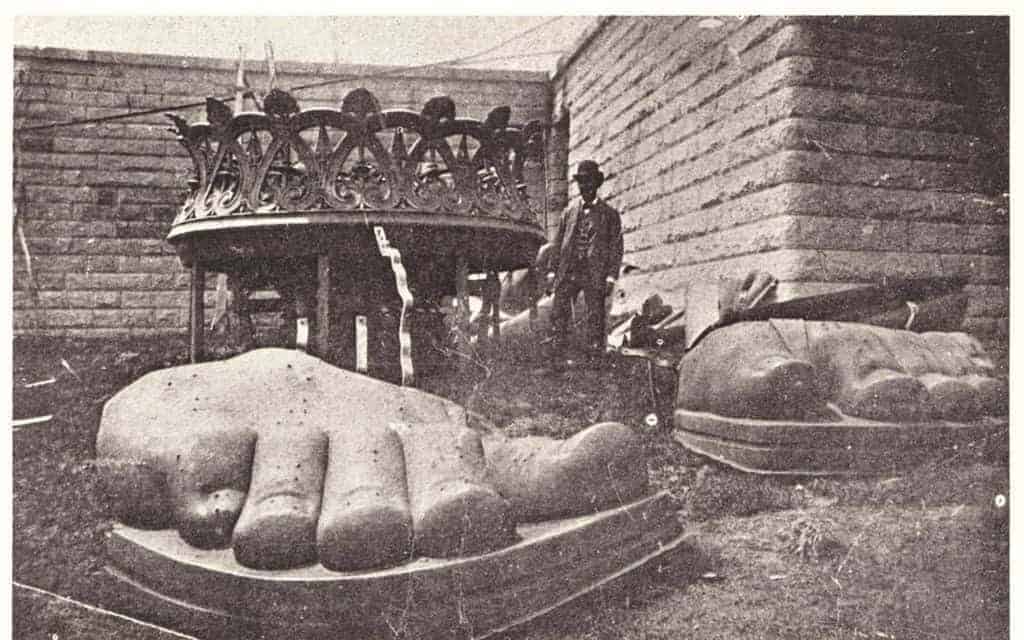

In 1875 the Franco-American Union was formed to solicit funds across France for the project. Bartholdi, despite not having yet decided on a final design for the entire statue, created the upraised arm and torch and the head and diadem. In 1876 the arm appeared at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, after which it was displayed in Madison Square in New York. American committees to raise the money for the pedestal were created. Bartholdi returned to France in 1877, taking the arm of the statue with him, to complete the design and have Eiffel build the final statue, of copper sheets connected by iron to a brick frame. President Grant issued an executive order allowing the United States to accept the French gift.

In France, the head was displayed at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, while various fundraising efforts helped finance the cost of construction, including the sale of tickets to watch as it was being created. By 1884 the statue was complete, and it remained in France while efforts to fund the base, which had lagged badly, were redoubled. The New York legislature passed funding for the effort only to have it vetoed by Governor Grover Cleveland. Other cities offered to pay for the pedestal if the statue were relocated to their community. In 1885 the statue was delivered, in crates, to New York, the shipping costs having been borne by the French. Meanwhile a fund drive led by Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World helped work on the pedestal move forward.

In April 1886 erection of the frame on the completed pedestal began, after which the copper sheets which comprise the statue’s outer surface were attached. In October the completed statue was dedicated at an event during which women were not allowed to attend the ceremonies on Bedloe Island due to concerns about overcrowding. Only two women – both French – were in attendance, somewhat ironic since the statue was of a woman. The Statue of Liberty has been modernized and modified several times over the years, as has the pedestal and what is now named Liberty Island. It is difficult to find a gift which came with more complications and difficulties.