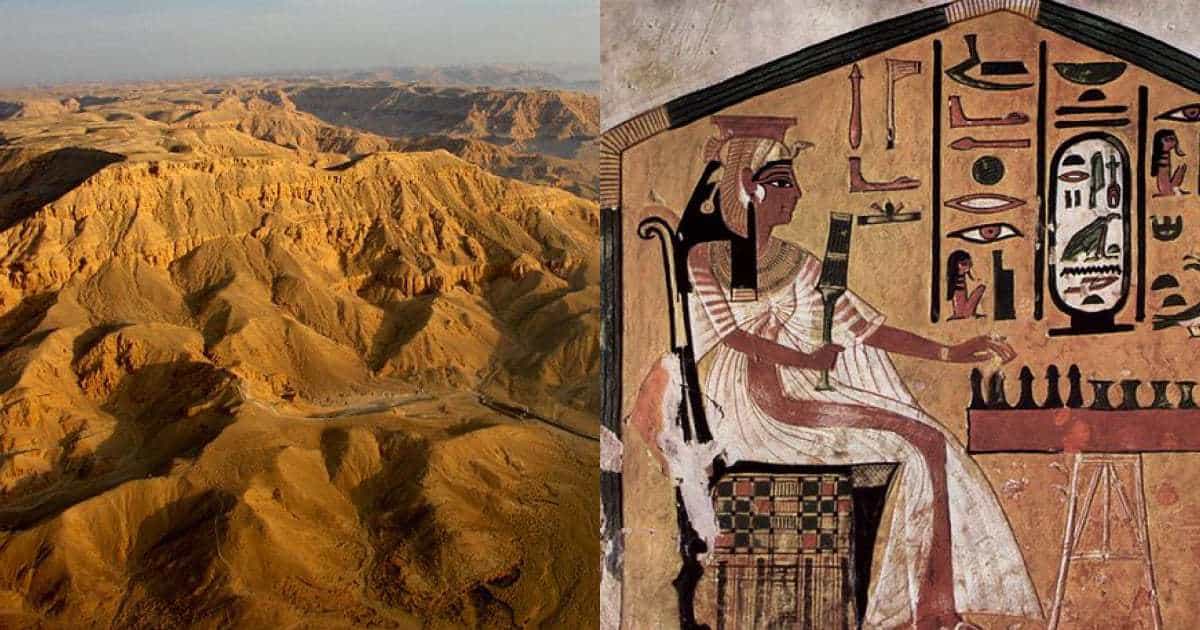

The Valley of the Queens is a busy Egyptian tourist attraction, yet its neighbor, the Valley of the Kings, often overshadows it. New Kingdom pharaohs who ruled Egypt from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth dynasties created the Valley of the Queens for the internments of members of the royal family and those who served them. Over the past century, archaeologists have conducted several conservation efforts to protect and study the burial ground. Discoveries using sophisticated modern techniques have revealed the site’s importance to the ancient Egyptians.

The Tombs Reflect Changes in New Kingdom Burial Practices

While its name suggests that the tombs were reserved for queens, there are more tombs designated to royal princes and princesses and nobles who served the royal family. The ancient Egyptians named the location Ta-Set-Neferu, traditionally translated as “the place of beauty.” Modern Egyptologists agree that another translation, “the place of the children of the pharaoh,” more accurately reflects the site’s initial purpose as an extension of the Valley of the Kings instead of a specific burial ground for royal consorts.

From the first dynasties, Egyptian pharaohs erected magnificent pyramids for their burials. This practice changed in the New Kingdom, with Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs choosing more isolated locations for their resting places. In the cliffs west of Thebes, laborers carved simple shaft tombs with little decoration that looked more like caves than resting places for royalty. Included in the tombs were items that the dead used in their daily lives, such as furniture, clothing, and cosmetic items, for use in the afterlife.

By the Nineteenth Dynasty, the tombs became more elaborate, with hallways, rooms, and burial chambers that became a celebration of the life of the deceased. Physical appearance was essential to the ancient Egyptians, and artists decorated the walls with images that represented the dead as they had looked in their youth, not as they appeared when they died. Nineteenth Dynasty tombs were filled with grave goods especially prepared for their journey into the afterlife, such as funerary texts, food, and drink.

While pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty used the Valley of the Queens as a burial ground for members of the royal family and the elite, this practice changed in the next dynasty. The pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty, also known as the Ramessid period named for the family that ruled Egypt, ordered their wives buried in the Valley of the Queens. Under Ramses II, only wives with the assigned title “Royal Bride” were allowed to be interred in the funerary complex.