The history of military rations – how the troops and sailors were fed – is a complicated one. Over time it has become about more than food and drink. Today psychological factors are considered as much as nutritional values. The quality and quantity of food contributes or detracts from morale as much as it does physical health. Two hundred years ago a typical US Navy sailor could look forward to a main meal of salt beef, salt pork, or pickled tongue, a porridge made of dried peas or lentils, hard biscuit known as hardtack, possibly some portable soup, and beer or wine to wash it down.

Today his counterpart can select, on larger ships, from a speed line resembling a fast food restaurant, or a main line offering choices which resemble a buffet. Fresh vegetables and fruit abound, along with assorted breads and rolls. There is a multitude of beverages available, though the Navy long ago did away with alcoholic beverages aboard its ships. Smaller ships and submarines have fewer options but still manage to provide choices at most meals, and nutritionally balanced options are always available. How the military’s feeding of its troops and sailors evolved extraordinarily over the years, especially following the introduction of the all-volunteer service.

Here are some of the ways the military was fed in the past, and how it has changed to what it is today.

Feeding the Continental Soldier

A continental breakfast today is usually coffee or tea, juice, and pastries or soft breads, with jam and fresh butter. A Continental soldier’s breakfast was not of that style. If he had the foresight to set aside some of the previous day’s bread for the morning that was his breakfast, usually taken with water or cider, possibly beer or spruce beer. Of course that assumes he had been issued a bread ration the day before, which all too often was not the case. If he had, it was likely hardtack, crackers baked to a hardness that it required soaking in liquid in order to bite into, even when it was not infested with maggots.

Congress had of course debated and then issued regulations for the feeding of its troops, but neglected to provide the funds to obtain the necessary rations, and to deliver them. A Continental recruit was promised generous portions of salt beef or pork daily, supplemented with vegetables, bread, milk, either rice or cornmeal, and a quart of beer per day. If beer was unavailable cider was offered. In truth the troops received far less. Often the only food they had was what they could forage or purchase, and since they were seldom paid they could purchase very little.

Jerked meat, including venison and other game, was often the only source of protein available. Regulations regarding hunting were often ignored, though game rapidly became scarce near major encampments. Pillaging food was against regulations, and punishments for stealing food included severe whippings (as much as 500 lashes), branding, riding the rail, or even death. Desertions because of hunger plagued the Continental Army throughout its existence. The records of the Continental Congress are filled with pleas from George Washington for rations for his troops.

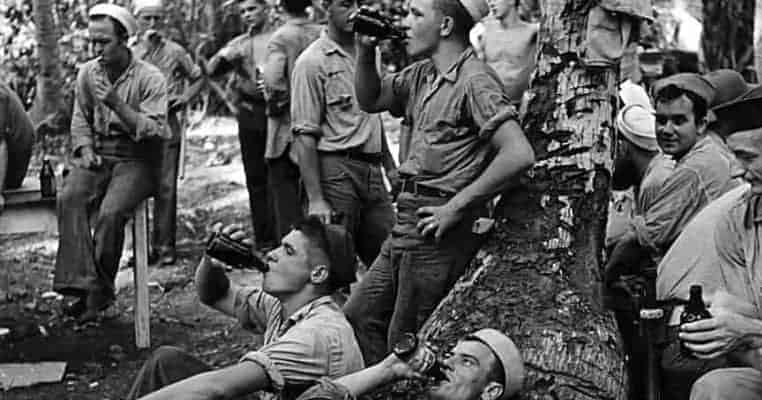

Sailors of the Continental Navy fared better because they obtained their supplies before leaving port and were often able to resupply from captured ships. Their diet was almost exclusively salt meat and dried peas (called pease at the time and referring to all dried beans and lentils) the juice of lemons and limes, and beer and rum. Water stored in wooden casks quickly became crawling with algae and other things, and was virtually undrinkable after just a few weeks at sea. Their officers purchased chickens, sheep, and sometimes pigs, carried onboard as a supply of fresh meat and eggs, and washed down their meals with wines and brandy.

During the Revolutionary War more soldiers died of the diseases associated with malnutrition than of battle wounds. When barrels of salt meat did arrive at the Continental Camps they were often short weighted, and the meat provided rancid, but it was issued to the troops anyway in lieu of nothing better. Dysentery and diarrhea, called the bloody flux, were rampant in the encampments. Conditions did not really improve as the war went on, in the 1780 Morristown encampment more men died than had at the more well-known Valley Forge winter. Congress passed legislation to increase the rations of the men in 1780, but as before did nothing to provide the food.