The first labor demonstration in what became the United States occurred more than a century and a half before the birth of the nation, when Polish craftsmen were brought to the Jamestown Colony to produce glassware and other products were denied the right to vote. The Poles went on strike in protest. Their importance to the success of the colony was such that the English settlers gave in to their demands, making North America’s first labor demonstration a successful one from the point of view of the aggrieved workers. The settlement was prompt and peaceful. The colony continued to prosper.

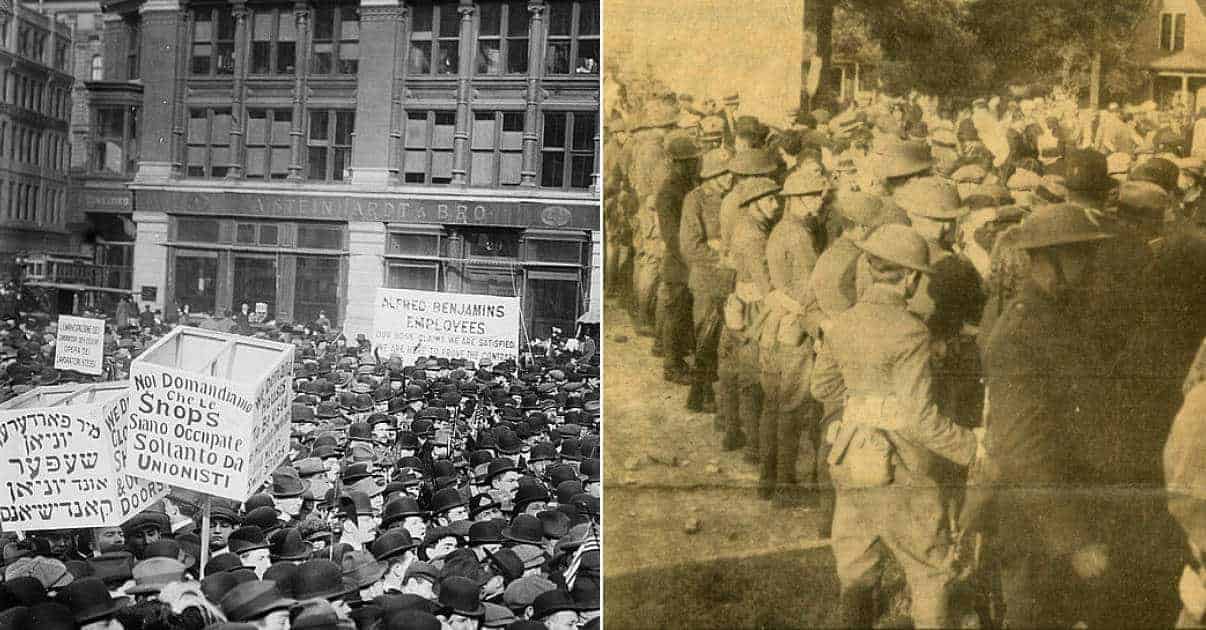

Throughout the 18th century, workers in different trades found it necessary to join together to petition their employers for redress of grievances. Indentured servants formed coalitions to seek relief via the courts, citing inadequate food from or living conditions. Skilled laborers such as shipbuilders and carpenters learned that standing together made it more likely to achieve concessions from employers in the areas of improved working conditions or higher wages. As corporations grew, workers unionized and their employers sought help from private security forces, local police, and federal troops to end strikes and prevent labor unions from gaining strength. Strikes often turned violent, and the violence often turned deadly.

Here are ten true stories of labor confrontations in American history, which changed the life of workers in the United States forever.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Panic of 1873 initiated a period of economic contraction which stretched well over five years, the longest such period of negative growth in American history, longer than even the Great Depression of the 1930s. During this period the railroads were particularly hard hit, as fewer goods were available to be shipped. In response to decreasing revenues the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road cut wages in 1875 and 1876. The following year, having seen little improvement in the financial situation, the B&O cut wages again. Railroad workers, who were then not yet unionized, responded by striking, beginning in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The strike soon spread throughout the system.

Workers refused to allow trains to be loaded, unloaded, or to move from the depots. West Virginia responded with state militia units, who refused to move the workers by force. The governor of West Virginia then requested federal troops. In Maryland, where strikers shut down rail operations in Cumberland, the Maryland National Guard was called up after lobbying of the governor by B&O President John Garret. The Guardsmen encountered protesters sympathetic to the strikers after mustering in Baltimore and fired into the crowd of “rioters”, leaving ten dead and more than two dozen injured.

The strike continued to spread, including to New York, where workers from outside the railroad industry joined with railroad workers attacking and destroying railroad property. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania workers struck the Pennsylvania Railroad. With local law enforcement expressing sympathy for the strikers the state mustered militia units to protect railroad property. Throughout the month of July, clashes between militia and workers led to the deaths of more than forty workers. At least twice that number were injured.

Strikers and sympathizers in Pittsburgh destroyed 39 buildings, damaged more than 100 train engines, and destroyed more than 1,200 railcars, before federal troops were dispatched to assist in bringing the violence under control. Late in July the chaos reached Chicago and other points in Illinois and Missouri. Throughout the summer railroad workers were joined by laborers from other industries as federal troops were sent to hot spots – ironically often traveling by rail – to suppress violence instigated by state militia, often encouraged by governors under the influence of the rail barons.

By the end of the summer the Great Railroad Strike and the violent reaction of state troops had led to the deaths of more than 100 people. Economic damage to the railroads was as high as $10 million ($220 million today) according to some estimates. The B&O attempted to implement changes for the benefit of the workers, largely to forestall more effective unionization nationwide. Workers and labor organizers recognized the power of workers operating together, and the drive for unionization gathered momentum.