Wars throughout history have been notable for the development of new methods of killing the enemy more efficiently. Humanity has not managed to evolve to the point where war becomes unnecessary, instead it has evolved the manner in which it is fought. Weapons have been developed, used and discarded when other weapons superseded them. Stronger defenses led to the development of more offensive power. Near instantaneous communications via satellite are in place, though infantry still have to rely on hand signals in tactical situations. Nearly every war has been marked with the first use of some new technology, or a new adaptation of old technology.

The American Civil War is often cited as the first in which the telegraph, railroads, and observation balloons were used. It was not, though their use was extensive, and in some ways revolutionary. Not all innovations from the battlefield were for destruction of the enemy either, the use of ambulances to transport injured and wounded to hospitals is a wartime invention which later entered civilian life. Many innovations lasted for centuries. No one can say for certain when the horse first appeared on the battlefield, for example, but they were still being used by European armies during World War II.

There are ten examples of the first use of weapons and equipment in war, and how they evolved .

Aerial Observation Balloons.

The Montgolfier brothers of France were the first to successfully fly a hot air balloon, an event witnessed by Benjamin Franklin. The Montgolfier brothers didn’t understand the science involved, believing that it was the smoke which provided the lifting power, but it worked despite their error. Its military value was quickly recognized by the French Army, which formed the Aerostatic Corps in 1794, tasked with using hot air balloons to observe the actions of enemy forces and to create accurate maps of the battlefield for the use of the commanders on the ground. It was the first Army Air Corps.

On June 2 1794 a hot air balloon was used for military purposes for the first time, observing the disposition of the Austrian forces near Fleurus. Officers ascended in the balloon for three days, making observations and preparing maps. On June 26 the French Revolutionary Army fought the Austrians in the Battle of Fleurus. The balloon remained aloft throughout the fighting, communicating with troops on the ground through the use of semaphore signals. Some messages were written and simply tossed to the troops waiting below. In this manner the French commanders received updates of the movements of Austrian troops otherwise out of their sight.

After the battle, which was a significant victory for the French, participants in the fighting thought the balloon had been effective, but bureaucrats in Paris were doubtful. Nonetheless a second company of the Aerostatic Corps was formed to work with the Army of the North, and that company made ascents prior to and during the battle of Mainz. That battle was a French defeat from a surprise Austrian assault, but French leaders on the field managed to extricate their army skillfully, preventing a rout, and the balloon observations were again credited with helping them assess the situation on the battlefield. Further observations were made as the French advanced through what is now Germany.

A company of the Aerostatic Corps accompanied Napoleon, then known as General Bonaparte, on his expedition to Egypt, but was destroyed while still aboard ship during the Battle of the Nile. Later in 1799 Bonaparte disbanded the remnants of the corps. Napoleon III activated balloon companies against the Austrians in 1859, and they contributed to the French victory over the armies of Emperor Franz Josef in a war which helped speed the unification of Italy. The French deployed balloons against the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, including during the siege of Paris, which ended in another French defeat.

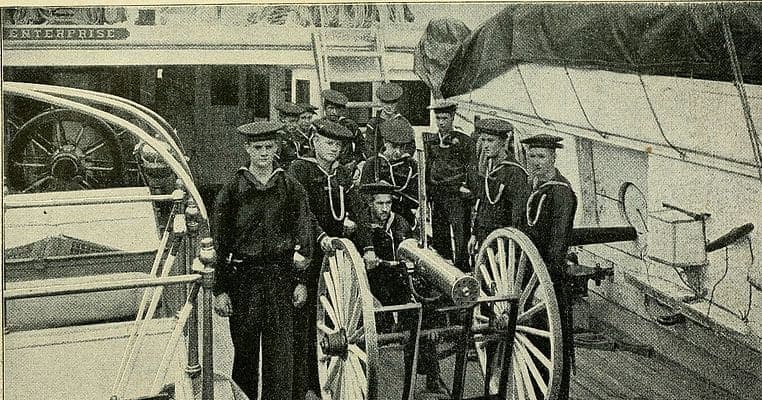

During the American Civil War observation balloons were used in the early years of the war by both sides, but by 1863 the Union balloon corps was dismissed. The Confederates never officially disbanded their balloon operations, but the lack of supplies caused by the Union blockade hampered their efforts. By the time Lee invaded Pennsylvania in 1863 the use of balloons on both sides was over, neither side deployed balloons for the remainder of the war. Both sides launched tethered observation balloons from the decks of ships, making the American Civil War the first in which a vessel used as an aircraft carrier was deployed.