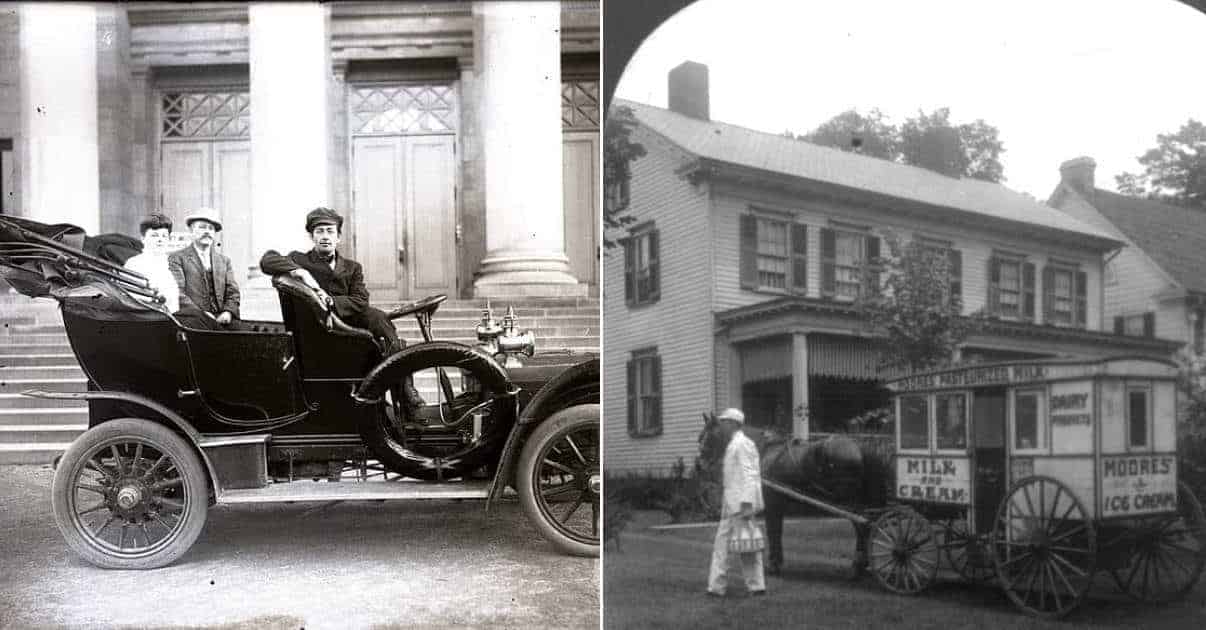

Those who sniff at electric and hydrogen powered vehicles because there is inadequate infrastructure to make them practical are ignoring a basic lesson of history. When gasoline powered automobiles were born there was no infrastructure to support them either. Outside of the cities there were few paved roads. There were no gasoline stations. For that matter there was very little gasoline. Towns were connected to each other by rail or by horse drawn coach. Some towns on streams relied on the water for conveyance to other destinations. Every town of any size had a blacksmith, even if it wasn’t a full time employment, but few had a mechanic of any sort.

The automobile created its own infrastructure and in so doing led to the demise of the infrastructure required of traveling by horseback. Industries were born and grew slowly and as they did others dwindled until they all but died. Many cities still maintain stables for the horses used by their police departments, but there are few liveries for the renting and stabling of horses in urban areas today. The automobile led to new industry and job creation as it also brought the demise of others.

Here are five beginnings and five endings for which we can thank the automobile.

Interurban Rail Companies

In the early twentieth century it was possible to travel between cities and their neighboring communities on self-propelled rail cars called interurbans. They were so prevalent that by changing systems when arriving in each city one could travel up and down the east coast from New England to Virginia using the interurbans of successive cities and their systems. Nearly all were electrically powered, connected to an overhead wire, and in some systems passengers could order meals, including breakfast made to order as they traveled.

The interurban meant that a businessman could travel in comfort between, for example, Indianapolis, Indiana and Cincinnati, Ohio, in almost any weather, without having to cope with the mostly unpaved roads and their interminable ruts and bumps, far more quickly than any horse drawn vehicle could convey him. If so desired he could return the same day. The main purpose of the interurban allowed smaller towns to connect with the business district of the nearest major city and many cities, Indianapolis for example, had rail lines emanating from its core like the multiple spokes of a wheel.

The interurbans sparked the growth of the suburbs and farther out towns and villages as they provided reliable and convenient travel into the city, allowing employees to move away from the often overcrowded and smoke filled environments which the city offered. Most could not survive solely on passenger fares, and many supplemented their income by carrying freight at rates which allowed farmers just outside of town an opportunity to deliver fresh produce and dairy products to urban markets each day.

The interurban companies were for the most part privately held and few made a great deal of money. The company owned or leased the rails and the cars which ran on them. In the early decades of the twentieth century car ownership increased rapidly and obliging local, state, and federal governments all turned their attention and the tax dollars they collected towards improving the streets and roads. It was soon less expensive and more convenient (and for many more fun) to use the car for the needs formerly met by the interurbans. One by one the companies that ran them folded, or switched to the use of buses.

By the late 1930s they were nearly all gone, although some lasted into the 1950s. Today some regions are relying on light rail systems to perform the function of the interurban railway, but there is nothing like the systems which were found when the interurban railways were so popular that they took most of the passenger traffic away from the cross country railroads. Many communities have created multipurpose recreational trails along the rail beds of the interurban railways which once served their cities, and some cities are exploring the feasibility of developing new interurban systems in the near future.