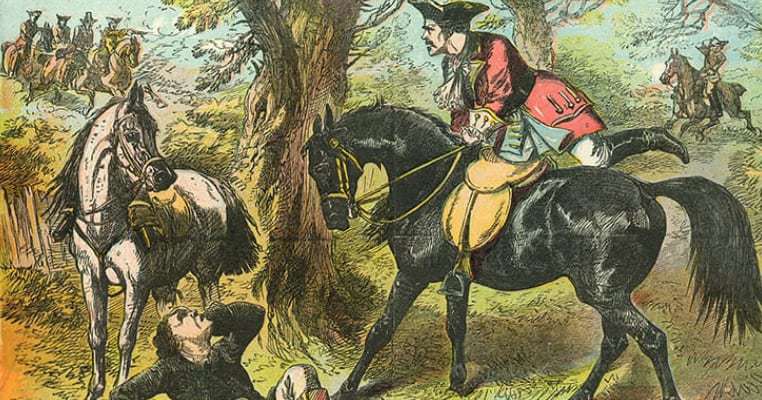

Dick Turpin (1705-39) was a dashing highwayman, an 18th-century Robin Hood who stole from the rich to give to the poor. His life was one of pluck and derring-do, conducted atop his loyal mare, Black Bess. He was also a snappy dresser, never seen without a tricorn hat, frock coat, and riding boots. He once rode 150 miles in a day, from London to York, to give himself a concrete alibi for a robbery, visiting many pubs along the way. Turpin defied corrupt officials, and broke ladies’ hearts whilst holding up their carriages in the most gallant manner imaginable.

Or so the story goes. In fact, almost everything in the preceding paragraph is nonsense of the highest order. This prevailing image of Dick Turpin is principally traceable to the novelist, William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-82). Ainsworth, like Sir Walter Scott and others, was a historical novelist, and in his most famous work, Rookwood, he created the version of Turpin imprinted upon the modern consciousness: ‘Rash daring was the main feature of Turpin’s character… with him expired the chivalrous spirit which animated so many knights of the road… that high devotion to the fairer sex’. Sadly, Ainsworth was no historian.

The real Dick Turpin was a repulsive, violent criminal, who did not scruple to discriminate between rich and poor. He murdered people, stole livestock, and subjected his victims to inconceivable levels of pain. Turpin died a criminal’s death entirely befitting one guilty of his offenses in the 18th century. In the following biographical sketch, you will find no romance, plucky opposition to the corrupt ruling classes, or good deeds. Instead, this article will present the real highwayman, warts and all: a hardened criminal, guilty of appalling actions, and with absolutely no remorse for his victims. Prepare to be shocked.

Early Life

Relatively little is known about Turpin’s early life. He was born in the village of Hempstead, Essex, which lies between Saffron Walden and the wonderfully-named Steeple Bumpstead. He was the fifth of six children born to John Turpin and his wife, Mary Elizabeth Parmenter, in 1705. John Turpin was a butcher, and also ran a pub at various points through his life as an extra source of income. Richard ‘Dick’ Turpin was baptised at St Andrew’s Church in the village on 21st September (see above), where William Harvey, the man who discovered the circulation in the blood, is buried.

It is thought that Dick followed his father into the trades of butchery and tavern-keeping. One tradition holds that he was an apprentice butcher in the nearby village of Whitechapel, but there is no corroborative evidence. Another suggests that he had a butcher’s shop in Thaxted, Essex, a few miles from Hempstead. It is uncertain whether he kept an inn, or where that might have been. He also supposedly married Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Millington, a maidservant, in 1725, though there are no parish records for it. Little else is known of Millington, apart from her later involvement in Turpin’s criminal activities.

Though we do not know precisely where, we do know that Turpin was a butcher as a young man. Butchers, of course, rely upon a supply of carcasses, from local farmers and traders, which they then turn into products ready for cooking. Throughout the history of crime in England, there have been butchers stocked by shady suppliers such as poachers and livestock-stealers. Turpin is one of those criminal butchers. In the early 1730s, Turpin began purchasing venison poached from the royal forests of Essex by a group usually known as the Essex Gang. This simple business arrangement changed Turpin’s life.