It isn’t only Army bases in the American south which were named after leaders of the Confederacy following the Civil War. Some military bases acquired their names as state National Guard Camps, and carried them over when they became active US Army installations. The US Army directly named others for Confederate leaders. The US Navy went even further. Naval warships bore the name of Confederate ships which sank Union vessels and killed Union sailors during the war. One such ship, USS Hunley, a submarine tender commissioned in 1962 bore the name of CSS Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy warship in battle, when it sank USS Housatonic in 1864.

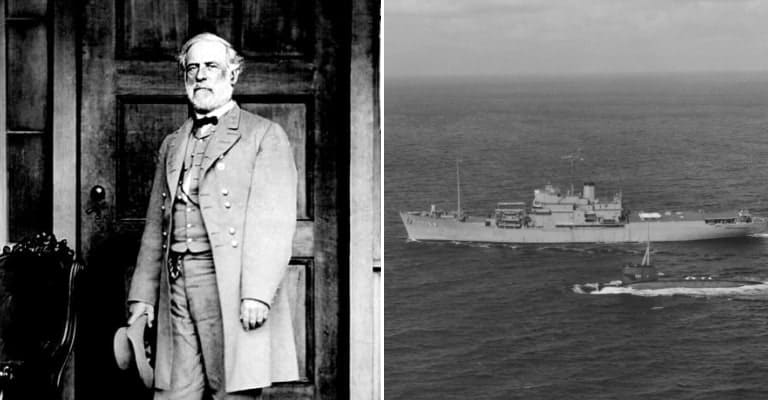

CSS Hunley was commanded by H. L. Dixon. In 1971 the US Navy named another submarine tender, USS Dixon, in his honor. Other naval ships named for Confederate leaders included USS Robert E. Lee, a nuclear ballistic missile submarine commissioned in 1960, and USS Stonewall Jackson, commissioned in 1964. Both of the ballistic missile submarines were part of the original “41 for Freedom” submarines designed to provide an underwater nuclear deterrent during the Cold War. The Navy has also named ships of war for Confederate victories on the battlefield, including USS Chancellorsville, named for the battle considered by historians and military tactics students as Robert E. Lee’s (and Jackson’s) masterpiece. Here is the story of the curious practice of the United States military honoring men who fought against it in the past, committing treason against the nation they had sworn an oath to protect.

1. Braxton Bragg, United States Army and Confederate States Army

Braxton Bragg graduated from West Point and accepted a commission into the United States Army in 1837, standing fifth in his class of fifty cadets. He served with distinction in the Seminole War, and further distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War. Though he was unpopular among his fellow officers, Bragg earned respect for the disciplined performance of the troops under his command. He returned to widespread admiration following the war, and in 1856 purchased a large sugar plantation near Thibodeaux, Louisiana. Bragg joined in local politics and government, accepted a commission as a Colonel in the Louisiana Militia, and grew in wealth and influence. At one time he and his wife owned over 100 slaves.

During the Civil War, Bragg renounced his oath and served in the Confederacy, mostly in the western departments. He commanded a corps at the bloody battle of Shiloh, and eventually assumed command of the Army of the Mississippi, later called the Army of Tennessee. He led his forces in several major battles, nearly all of them defeats for the Confederacy, though he did win a morale-boosting victory at the Battle of Chickamauga. Bragg failed to adequately follow up on his victory, and suffered a severe defeat at the subsequent battles for Chattanooga. Regarded by most historians and military scholars as an ineffective leader and tactician, Bragg’s war ended with him having lost the confidence of Confederate military and political leaders, though he remained in the field until captured in May, 1865.